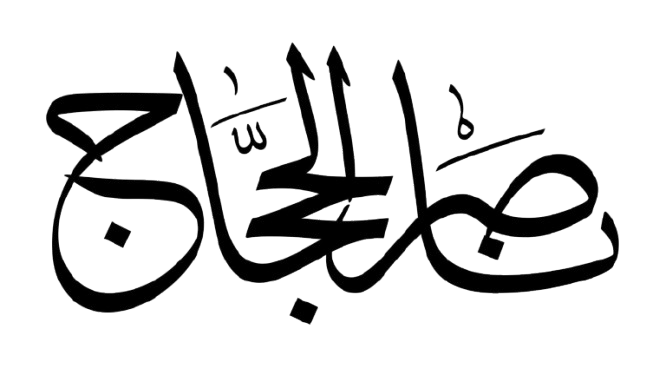

Safaa Dhiab

With this poem, poet Nasser Hajjaj opened the tribute session held for him on Saturday morning at the Union of Writers and Authors in Basra. The session, presented by poet Mohammed Saleh Abdul Ridha, featured a reading of several of Hajjaj’s poems reflecting a creative journey that began in the 1990s and continues to this day. He has recently published his poetry collection Mongrels of Troy (Kilāb Ṭarūda).

Poet Talib Abdul Aziz spoke about Hajjaj’s poetic experience, saying:

“We must return to the early years of acquaintance – about ten years ago when we worked together at Radio Sawa: he was in his second homeland, America, and I was in Basra. I used to hear his reports on the radio and wondered if I would ever meet him. Later, he came to Basra; we exchanged visits and conversations. I came to know him as both a poet and a journalist – and as a student at the American University, until he completed his PhD in Beirut.”

Abdul Aziz continued:

“We’ve just listened to poems ranging across classical meter, free verse, and prose poetry. It seems that abundant knowledge sometimes erodes the poet’s edge. I do not wish to judge how a poet can write a classical qaṣīda here and a prose poem elsewhere – but this invites critical reflection. Personally, I admire a poet who masters the art of both: who gives us a magnificent, powerful classical poem, and beside it, a prose poem that stands shoulder to shoulder with it.

“In the poems we just heard, I found that explaining weakens listening – perhaps Hajjaj has brought us something new. In Basra, we do not explain or clarify; we let the poem speak for itself. Perhaps Hajjaj’s cultural background differs from ours, and I noticed that the audience responded more to the metrical poems than to the others – their inclination toward rhythm was stronger. The texts we heard confirm that if Hajjaj were granted a tranquil and stable home, we would hear poems very different from these. The years of exile, searching, and living between many places have cast their shadow over his poetic spirit.

“I also wish to speak of Hajjaj’s Basrian identity. He is among those who encourage me to embrace this belonging. He was one of the initiators of a cultural project to establish a ‘Jahiz Street’ in Basra – a street dedicated to culture – though, unfortunately, that project has yet to see the light.”

Poet Kazem Hajjaj (a relative of the honoree) added:

“In a previous talk, I spoke about the districts of Basra. I said that when cities were first founded, they began with a dār al-qaḍāʾ a courthouse – and from this came the term qaḍāʾ (district). What distinguishes Basra is that each of its districts has given Iraq a distinct creative legacy:

Shatt al-Arab District produced great singers and musicians – Majid Al-Ali, Fouad Salem, Riyadh Ahmed.

Abu al-Khasib District, the rural district, gave us great poets – Badr Shakir al-Sayyab, Saadi Youssef, Talib Abdul Aziz, Mustafa Abdullah.

Qurna, however, is different – I have always thought of Qurna as the most Sumerian of all, situated at the threshold of the marshes, more Sumerian than rural-Basran. Hence, it produced scholars and thinkers rather than poets – Nouri Jaafar, Faisal al-Samer, Ahmed Orabi – people distant from poetry.

“I used to believe that these areas had produced only two poets – Kazem Hajjaj and Fawzi al-Saad – until I discovered that my cousin Nasser Hajjaj was writing poetry. He demolished that theory which claimed that Qurna, Huwair, and Madinah were scientific towns more than poetic ones.

“Nasser Hajjaj carries within him a Levantine poetic spirit more than an Iraqi one – softer and more lyrical. The Iraqi poetic spirit, despite its grandeur, tends to be massive and solemn, producing poets like Al-Mutanabbi and Al-Jawahiri – poets like stones – while Levantine poetry and song are gentler, more loving, more fluid in language.

“Thus, Hajjaj, the poet who comes from northern Sumerian Basra, embodies a Levantine lyricism within a Basran soul.”